This is the last installment on the ins and outs of the most expensive helmet decorations in the universe.

This is the last installment on the ins and outs of the most expensive helmet decorations in the universe.

Made from scraps: Over the years, I have read and heard much yammering about covers and caps being made from scraps left over from smock production, attempting to explain the tendency for the use of parts in multiple shades and patterns on most Waffen-SS camo items. There are two reasons this is not likely nor even feasible.

First, most garment manufacturers specialize in one or two types of garments. Cap companies make caps, tent companies make tents (and shelter quarters) and garment companies often make just one thing- such as shirts or jackets or trousers- a few make multiple items, but it’s very common for it to be one. This is for reasons of efficiency as they literally count every second of production time when computing their costs. Thus it’s very probable that these items were not made in the same places.

Second, and more importantly, efficient cutting is one of the most important aspects to garment manufacture. The scraps remaining from cutting smocks and Zeltbahns are minimal- typically just slivers. I know because I’ve personally laid out the patterns and cut them.

Shading: It’s extremely rare to find original covers (or any WWII German camo) on which all parts are the identical shade or even pattern. The logical explanation for the mixed shades is quite simple.

In factories, fabric is cut many layers deep (up to 100) with a power knife or dies. To do a spread on a cutting table typically requires multiple rolls of fabric, and even the same run of fabric will have shade changes. When one has thousands of parts, in multiple shades, from multiple cuts, keeping them in matching color order is a nightmare and was obviously not a requirement.

Markings: Occasionally, one does find legitimate markings on original covers. These are exclusively related to the size of the cover. I have never, ever seen a maker mark, a year nor the much sought after Buffalo Wings stamp.

If marked, one usually finds an Arabic 1, 2 or 3 stamped in black or violet ink, typically toward the rear of the cover. Others have the size range of the liner, such as 56-59. The handful of those I have encountered were stamped on the lower front. Most covers are unmarked.

Profile: Some ado has been made about how the cover follows the profile of the helmet- namely along the lower edge of the sides. This is more a reenactor argument than one among collectors.

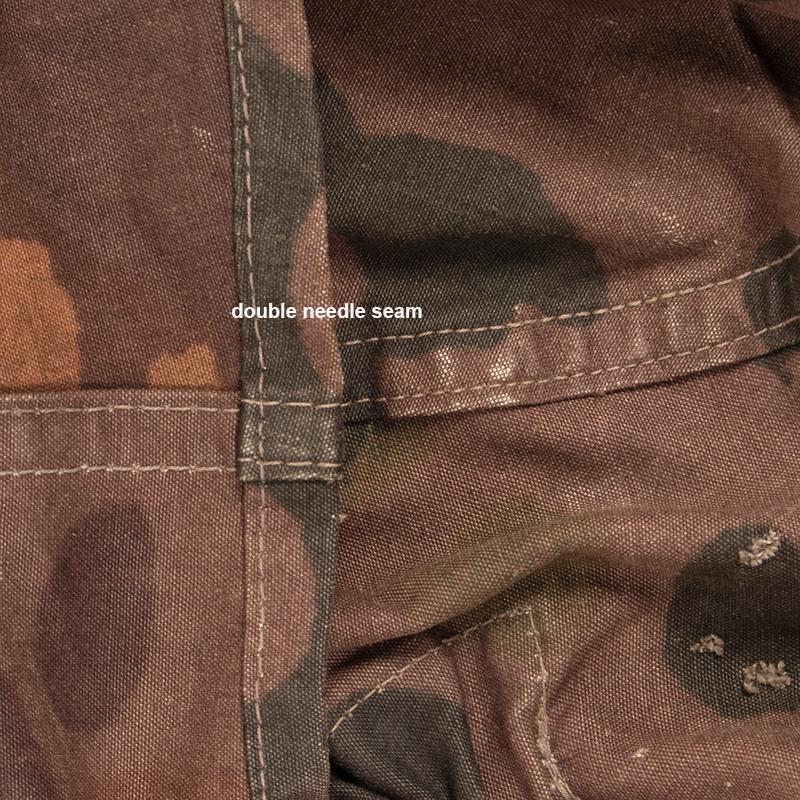

Double needle seams: Some WWII covers are made using a two-needle machine. One will see two perfectly parallel rows of stitches on both sides of the fabric on the two seams that join the center panel to the sides. Many covers were also made with normal single need machines which produce one visible row of stitching on one side and two imperfectly parallel rows on the other.

I have never seen true double needle stitching on a reproduction. Not yet anyway.

Note that at least one faker has attempted to recreate the two-needle stitch with a single needle machine. This produces two visible rows on both sides, but it’s impossible to keep them perfectly parallel. Look for railroad tracks- even when they curve, they stay evenly spaced. If one finds an imitation double needle stitch, the item is fake. Period.

Original spring covers are typically folded by rotating the piece rather than sides and ends together. Why? It may be a few seconds faster.

Spring Covers: The rectangular covers that encase the rocker clips vary in width and length and are frequently a different shade or pattern than the main panels. On a few helmet covers I have seen, one or more of the spring covers was flipped green side out.

.

A very well made fake, but the maker cut the fabric on the bias (diagonally to the grain.)

Direction of grain: The weave of a fabric creates a “grain”. In the case of helmet covers, the fibers of the cotton poplin run horizontally and vertically. Standard practice is to cut parts either perpendicularly or parallel to the sides of the cloth. If cut diagonally, the parts tend to stretch and deform when sewn making the ends not meet evenly and so forth. Cutting parts diagonally to the grain is referred to as “on the bias”. Parts that do need to stretch, such as sleeve binding and neck bands are cut this way.

This is hard! Sadly, if someone is skillful, has real fabric (a Zeltbahn), and excellent repro clips (or original) it can be very difficult to discern a fake. There is no easy-one-and-only-magic bullet. The determination of yay or nay is made by observing multiple details. I remain undecided on probably 10-20% of the covers I handle.

Summation: As with many things, your first warning is always “too good to be true”. A real cover for $1500 that’s been on ebay for 6 months is not real. (In 25 years I’ve seen a grand total of ONE real cover on ebay- and that was in the last year.)