The basic silhouette of the Stahlhelm is immediately recognizable as an imposing symbol of force, so recognizable in fact that it’s said that it even influenced the design of Darth Vader’s helmet.

But this WW2 German helmet (which has been called one of the most effective steel helmet designs in history) has origins that go much farther back than World War II. Here’s a basic primer.

The Origins of the Stahlhelm

The first Stahlelm was not the M42 or even the M35 Stahlhelm; that would be the M16 Stahlhelm.

Consider this – you’re a recruit serving on the Western Front of the First World War in France. This is one of the first major modern wars, complete with breech-loading artillery, chemical weapons, and tanks.

Protective gear for conscripts, shall we call it, was somewhat lacking. At the beginning of the war, soldiers wore leather helmets.

Which were, as you might imagine, sorely deficient when it came to turning shrapnel and shot. Head wounds on the Western Front were a major casualty, and something had to give.

However, the first steel helmet innovation actually came from the other side of No Man’s Land – the English and the French were the first to deploy the steel Brodie (AKA Tommy Helmet) and Adrian helmets, respectively.

The Germans recognized the need for a better helmet too, and their testing began at the end of 1915. What they came up with was based off of a Medieval design known as the sallet, which was commonly used in Western and Northern Europe through the 1400s and 1500s.

By 1916, the first M16 Stahlhelm helmets were issued to German Sturmtruppen before the Battle of Verdun, and by 1917 they were widely issued to Imperial German troops along the Western Front.

The M16 Stahlhelm was made of a hard martensitic steel, which increased production costs but also increased protection. The design also had a low visor and a broad skirt that covered the nape of the neck. Consequently, the Stahlhelm provided excellent protection to the front, sides, and back of the head, as well as the base of the skull and neck.

Also, as you can imagine, the steel helmet provided far superior protection against shrapnel and small arms fire than any leather headcover would.

It was this basic design that continued to be used in Imperial Germany as well as through the interwar years and during the Second World War. It also takes a practiced eye to tell the difference between an M16 Stahlhelm and the WW2 German helmets that replaced it, which also go by the moniker “Stahlhelm.”

Improvements to the M16, Yielding the Equally Familiar WW2 German Helmets

While the M35 Stahlhelm is better known than the M17/M18, these were the ones that replaced it and which were used during the postwar (that is, post WWI) years.

By the early 30s, it was recognized that the earlier Stahlhelm needed any overhaul in order to support more mobile troops, while also being more effective at protecting the wearer against small arms fire.

And so we come to the development of the M35 Stahlhelm, possibly the most famous of the WW2 German helmets.

The M35 Stahlhelm was more compact, with a smaller skirt at the back of the neck, but it was also thicker and denser, so as to provide better protection against fire and impact. It was made of high-carbon steel with the addition of some molybdenum and formed from steel sheets that were between 1 and 1.5mm thick.

About Our M35 Stahlhelm Helmets

Our reproduction M35 Stahlhelm helmets are some of the best in the market and come in at an attractive price.

They are modeled after the original M35 Stahlhelm that was standard issue to all German troops before the Battle of France, and our reproductions are finished in the flat Feldgrau (field gray) of the originals, so there’s no need to repaint them.

The weight and thickness of these M35 Stahlhelm reproductions also closely matches the originals and they come with liners and chinstraps.

About Our M42 Stahlhelm Helmets

The 1942, or M42 Stahlhelm, was a refinement on the Stahlhelm design that would help reduce costs. The rolled edge along the helmet was eliminated, producing a rough edge, and the protection offered by the base of the skirt was reduced slightly. To reduce costs, the ventilation holes in the M42 Stahlhelm were stamped directly onto the shell. Also, originals were made with a lower quality steel than the alloy used to produce M35 and M40 Stahlhelm helmets.

Our M42 Stahlhelm reproductions are modeled after the originals that were issued to all branches of the German military during the Second World War. They are similar in size and weight to the originals and like our M35 reproductions are finished in the original Feldgrau, so there is no need to repaint them.

Questions About Our German WW2 Helmet Reproductions

Want to learn more about these German WW2 helmet reproductions? Check each product listing or get in touch with us at 270-384-1965. We’ll let you know about the product specifications and how they capture the details of the originals (as well as where they differ).

This is the last installment on the ins and outs of the most expensive helmet decorations in the universe.

This is the last installment on the ins and outs of the most expensive helmet decorations in the universe.

The two original covers used for our patterns.

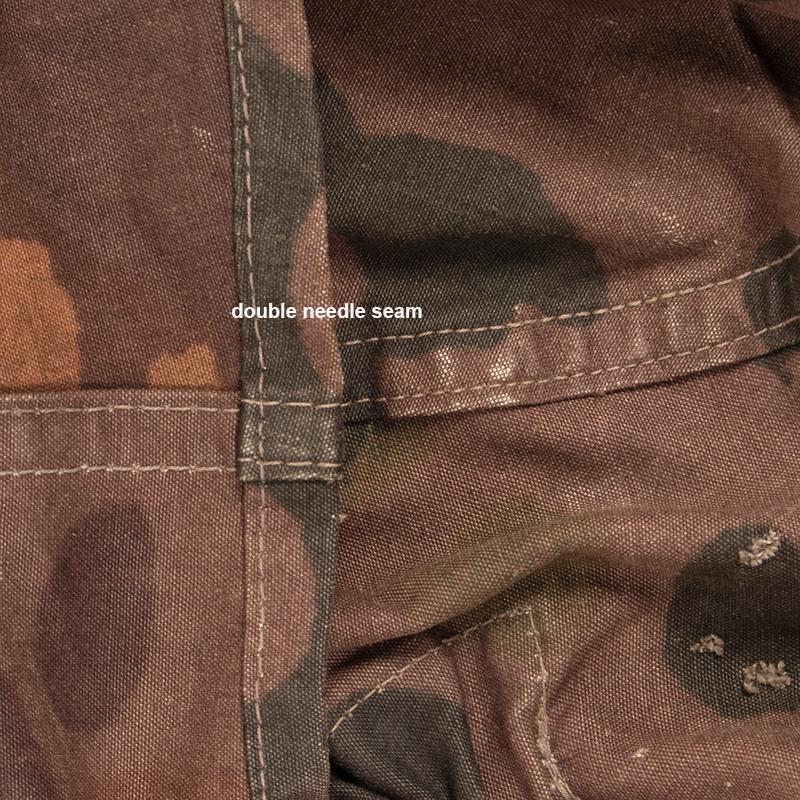

The two original covers used for our patterns. The three main panels of a cover

The three main panels of a cover

One punch = 30 panels

One punch = 30 panels