Copied from the Quartermaster Foundation Page

Harold P. Godwin

The Quartermaster Review

May-June 1945

Looking at today’s trim, well-fitted GIs, a soldier of World War I must wonder, when he remembers the day he was bundled into his serviceable but none-too-snappy uniform, with its peasant brogans and its wind-up puttees, how it is possible to turn out the well-dressed soldier of today, especially in view of the many more millions now being clothed and equipped. In his day there were said to be only two sizes of Army clothing-too large and too small. What makes the difference?

The answer lies in the meticulous care and great lengths to which the Office of The Quartermaster General has gone in this war to make our troops the best-dressed Army in the world, not only sartorially but from the standpoint of comfort and protection.

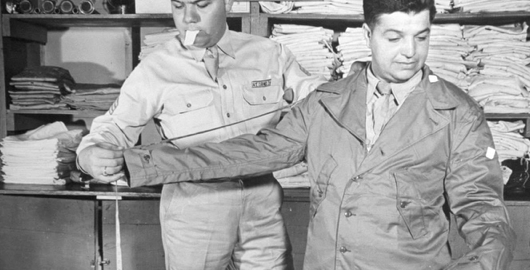

The new soldier wears new clothes in a new way. What’s more, they fit. Today, when the incoming soldier appears at the clothing counter of a reception center, his measurements are carefully taken, his proper clothing is drawn to those measurements (sixty-six items in all), and a professional tailor then sets to work to give an almost custom-made trimness to an issue uniform. But thanks to the careful compilation of measurements and other research, there are usually sizes on hand to fit most inductees with little, if any, additional tailoring. Today approximately 6,000 different sizes of various items of clothing and footwear are stocked and issued by the Quartermaster Corps in ratios arrived at by experience.

The task confronting the OQMG in clothing and equipping the prospective Army on October 16, 1940, when the first registrations under Selective Service began, was one for which there were no precedents or adequate schedules. The only information available was in an Army Regulation published in 1937, but that had been compiled from the size requirements of our small peace-time Army and was in no way applicable to the needs of the rapidly growing Army which was being inducted from civilian life. Records from World War I were useless because of the differences in the basic garments.

The first registration embraced men between the ages of twenty-one and thirty-five. As the rigid requirements of the Army had to be lowered considerably for Selective Service, the Office of The Quartermaster General had to look to civilian sources for information as to the sizes which would be required for men in the twenty-one to thirty-five age brackets. Such information was obtained from the nation’s chain store organizations and mail order houses, whose volume of country-wide distribution would, it was thought, provide a fair representation of the sizes of clothing being sold throughout the United States. From this information size tariffs were prepared, and they proved exceedingly helpful as a starter.

The draft picture in 1941 upset the apple-cart. It meant that new and more explicit information was needed to provide effective tariffs. This was obtained by a procedure requiring that a copy of the initial clothing size form for each inductee be sent to the Office of The Quartermaster General.

January, 1942, brought still another change in the draft ages, but one which was not to be effective from a clothing size standpoint until early in 1943. Legislation was enacted requiring the induction of youths from eighteen years up, and simultaneously rescinding the order for taking men over thirty-eight. The effect of this upon the existing size tariffs was immediately anticipated, and the OQMG sent letters to approximately seventy-five leading educational institutions having ROTC units for information on the sizes of clothing required by college youths within the age group of eighteen to twenty years. This information resulted in further revised tariffs, which showed an increase in the smaller sizes and a comparable scaling down of the larger sizes.

By September 1943 the sizes of more than 6,000,000 individuals had been tabulated, studied, and again made into new tariff lists. At this time the procedure requiring that a copy of the individual measurements be sent to the OQMG was discontinued because maintenance requirements had then grown larger than initial issue requirements.

However, even now, the tariffs thus tabulated do not remain static. Semi-monthly reports from points where clothing is issued are constantly checked against the tariff lists. In this way tariffs are kept up-to-date and in conformance with any changes which might appear in size trends.

One of the problems which presented some difficulty at first was that, in many instances, men had to be held at reception centers because their unusual stature required special-measurement clothing not provided for in the regular tariffs. To meet this situation a group of sizes, known to the commercial trade as “extra size” garments, were provided, but were designated as “supplemental” sizes. Experience has proved that only small quantities of these sizes need be placed at the reception centers to eliminate delays. Reports from the Philadelphia Quartermaster Depot show that the provision of these “extra sizes” has reduced the necessity for providing special made-to-measure clothing by more than seventy-five per cent.

But even with these provisions exceptions will crop up and special clothing must be made. A cook in the 102nd Cavalry required trousers with a 48″ waist and a 31″ length. A boy at Fort Knox had to have a 5-EE shoe for one foot and a size 8-E for the other, and there was a trainee at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, whose bull neck required a shirt with a 19″ neckband. The periodical check on the tariffs as new inductees came into the Army revealed that they were not working uniformly in all sections of the country. An immediate analysis was made and it was found that a difference in average stature prevailed in different geographical sections. Men along the northeastern Atlantic seaboard run to stocky builds and short height, while those inducted in the southern area are taller and more slender. The middle west inductees are men of medium stature, generally requiring more of the medium-to-large sizes, while on the west coast are found a combination of all sizes on an equal basis.

In view of these findings a procedure was established in May 1944 whereby camps, posts, and stations were authorized to establish stock levels of sizes and maintain inventories based on their individual experiences. This procedure has worked very well. A recent poll, taken among thousands of service men, revealed that nearly eighty per cent of all the clothing, and eighty-six per cent of the shoes, fitted perfectly, even by rigid Army standards. The accuracy of the size ratios is proved by the fact that no surplus of either the standard or the unusual sizes is piling up.

In order to achieve this balance and have adequate stocks to equip all inductees without delays, an infinite variety of sizes must be kept on hand. Ninety different shoe sizes are stocked in proportions indicated by the tariff ratios. Thirty different sizes of trousers are carried in regular stock, and twenty-two different sizes of shirts.

Data compiled for millions of inductees shows the following to be the actual measurements of the “average” newcomer to the Army as he appears at the clothing counter of a reception center: 5′ 8″ tall; 144 pounds in weight; 33 ¼” chest measurement; 31″ waist measurement. From the tariff tables showing the frequency of size issues it is found that the sizes most frequently issued are a 7 to 7½ hat, number 9 gloves, a 15 shirt with a 33″ sleeve, a 36 regular jacket, a pair of trousers with a 32″ waist and a 32″ leg length, size 11 socks, and size 9-D shoes. These figures may be taken to indicate the size of the “average American young man.

Up until recently there had been no Army regulations developed specifically for the fitting of clothes for women. However, data has been compiled for women through the same procedure followed in the case of male inductees-the tabulation of the initial measurements at the time of enlistment. This information, however, could not be used as conclusive because it was found that most women gained weight after enlistment and training. In order to obtain workable tariffs on women’s sizes, data is now being compiled from a canvass of approximately 12,000 Army nurses on duty throughout the United States. Similar action was recently taken with 30,000 Wacs.

As in the case of men, the information on women’s sizes obtained from the clothing trade did not apply to Army uniforms. Commercial size tables were geared to one-piece dresses, for the most part, and were not applicable. The tariffs set up from the recent surveys revealed that size variations among women were much greater than in the male group. The smallest woman soldier is 4′ 7 ½’ tall and weighs 77 pounds. Her contrasting colleague is 6 feet tall, weighing 224 pounds. Though the minimum height and weight for Wacs is 5 feet and 100 pounds, an exception has been made for women of Oriental descent, whose normal height is usually below the minimum.

The predominant size of the typical woman soldier, as shown by the tariffs, is 5′ 4″ in height and 128 pounds in weight. She has a waist circumference of 26 1/2 inches, wears a 22 hat size, and a 6-B shoe. Instead of being the traditional “perfect thirty-six” she takes a size 14 jacket. The collar of her O.D. shirt is 13 inches, and her ankles are neatly encased in size 9 1/2 rayon stockings.

Blue and red pencil marks on original MP40 pouches.

Blue and red pencil marks on original MP40 pouches. Original smock with chalk marks…how can they be wrong?

Original smock with chalk marks…how can they be wrong? All those squares, U’s, tick marks, dots, dashes and other blemishes were applied at the factory in WWII to show the workers where to sew the parts- not offend the tender sensitivities of those keeping history alive 80 years later.

All those squares, U’s, tick marks, dots, dashes and other blemishes were applied at the factory in WWII to show the workers where to sew the parts- not offend the tender sensitivities of those keeping history alive 80 years later. Various stamps on the parts of original MP44 pouches.

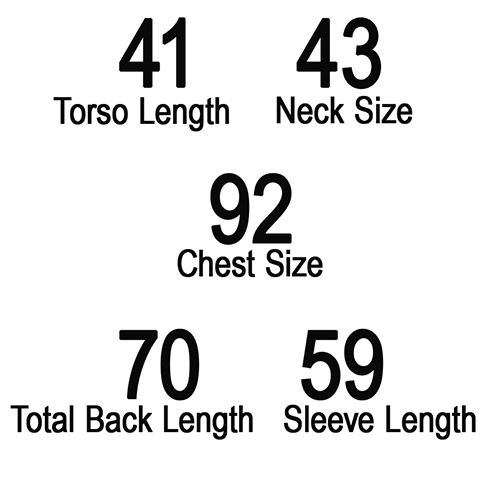

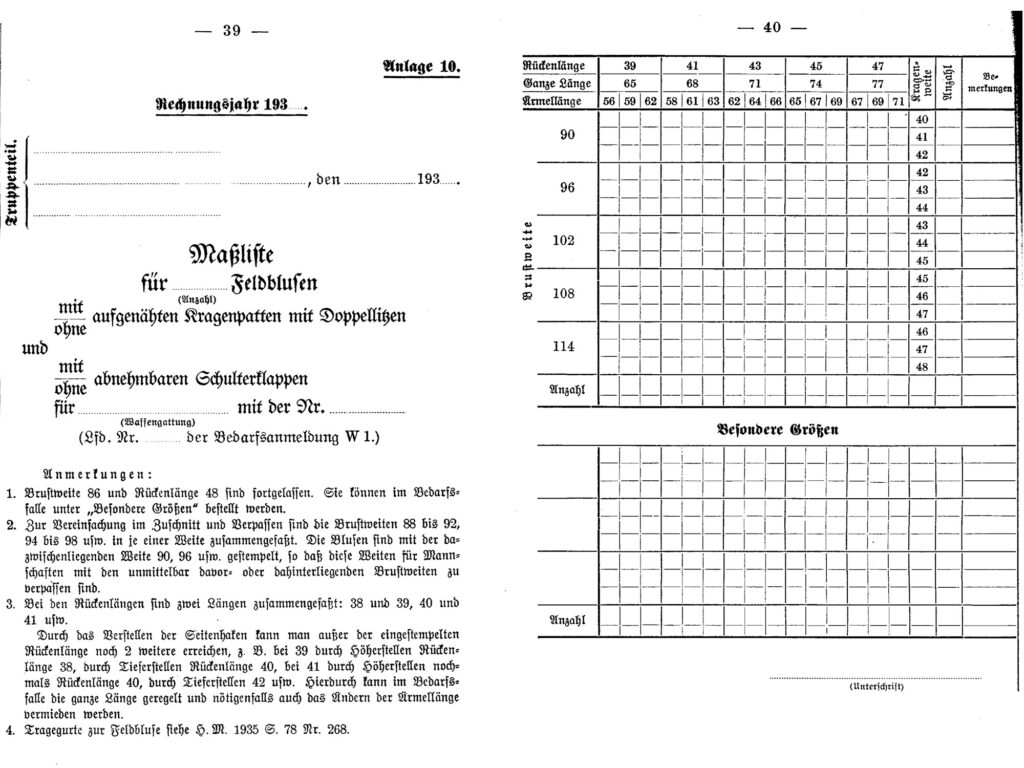

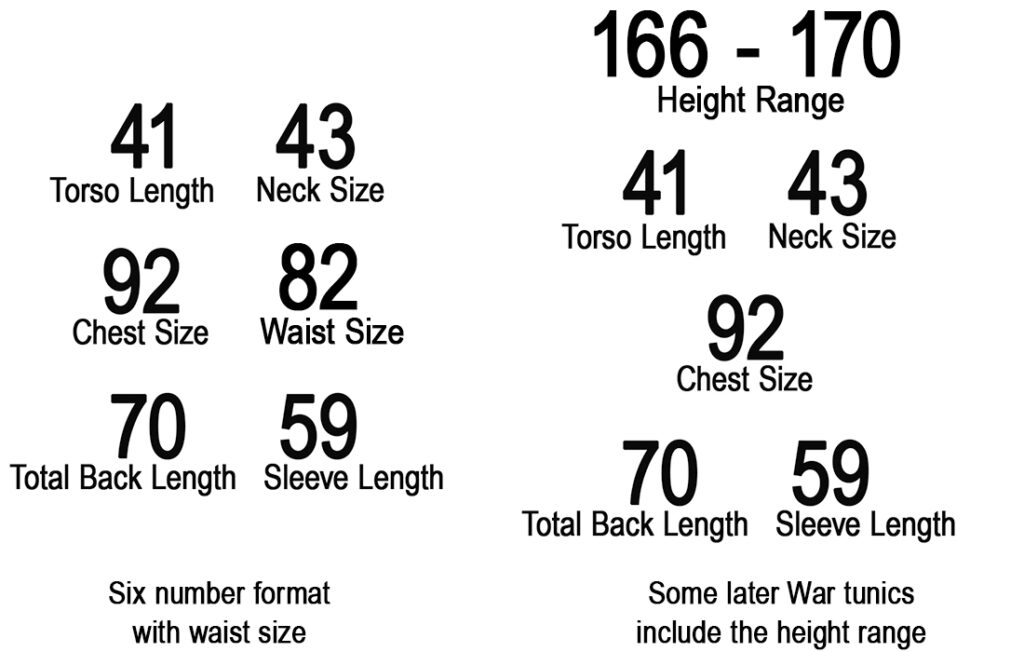

Various stamps on the parts of original MP44 pouches. Shade marks (“226”) were stamped in black ink on all the wool parts of this original WSS M41 Feldbluse to indicate the layer of fabric they were cut from. The cloth wouldn’t have been stacked 200+ layers deep- but there were likely multiple cuts on the same table being done that day, so this might represent 2nd cut, layer 26 or something similar.

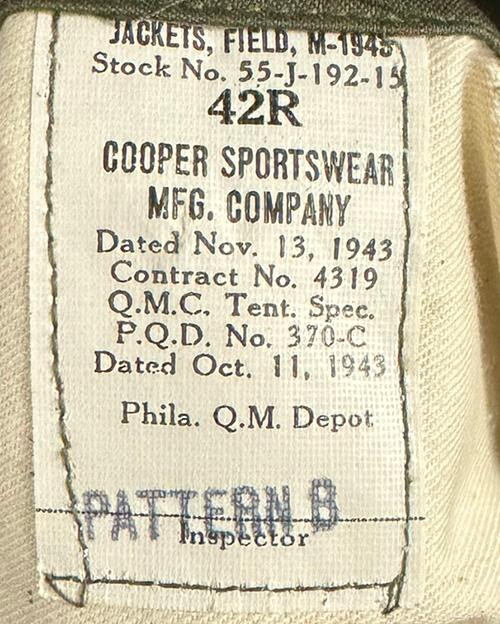

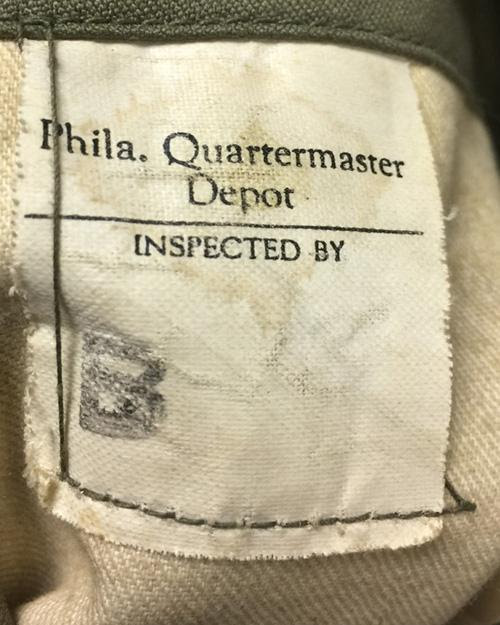

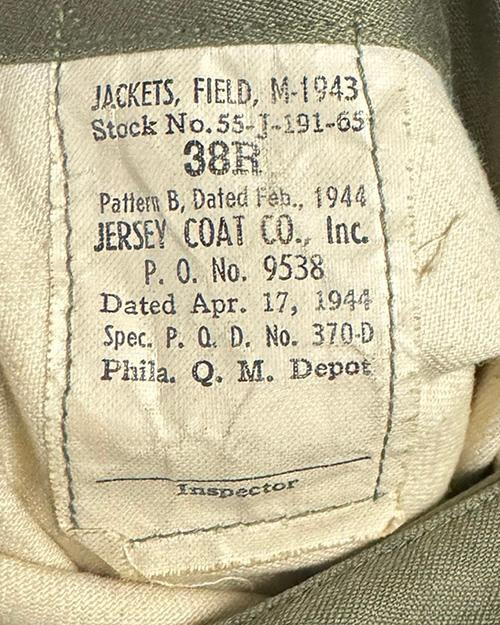

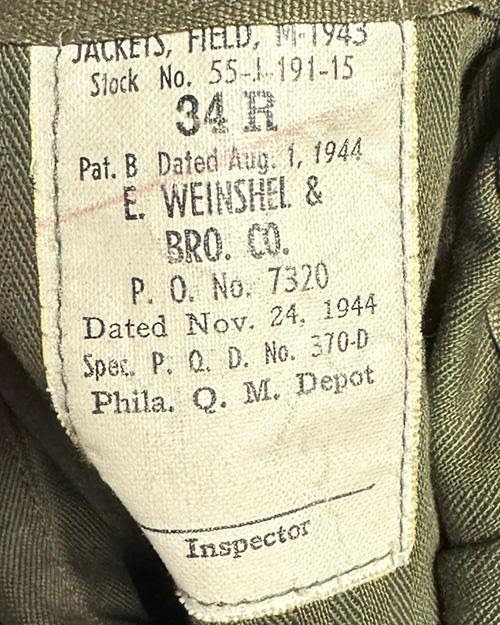

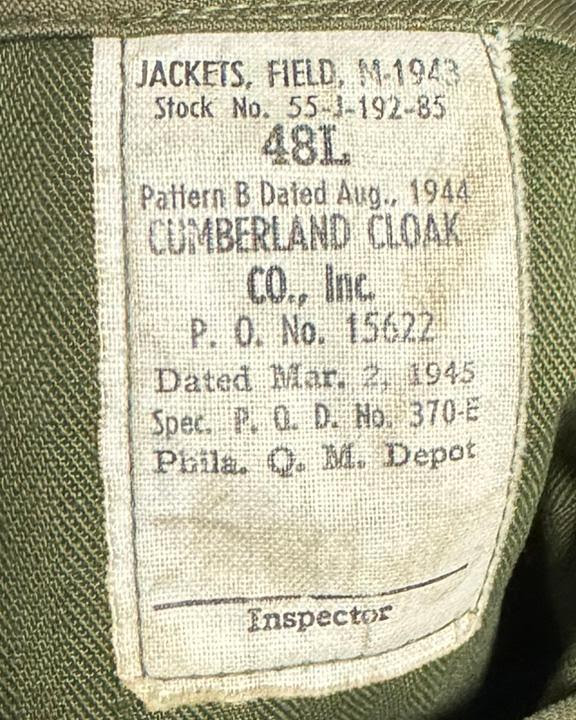

Shade marks (“226”) were stamped in black ink on all the wool parts of this original WSS M41 Feldbluse to indicate the layer of fabric they were cut from. The cloth wouldn’t have been stacked 200+ layers deep- but there were likely multiple cuts on the same table being done that day, so this might represent 2nd cut, layer 26 or something similar. Shade tag on a original jump jacket. 09 is likely the layer, 36R the size, and the other two numbers could be any number of things. The info on the tags varies from factory to factory.

Shade tag on a original jump jacket. 09 is likely the layer, 36R the size, and the other two numbers could be any number of things. The info on the tags varies from factory to factory. Inside flap of original MP44 pouches. We assume the “CON” is the first part of “Continental” (a major rubber and tire maker) as that’s what these flap sides are made from.

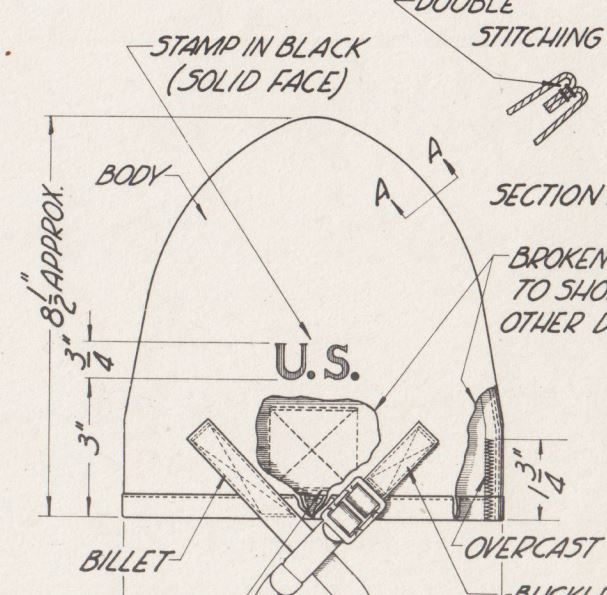

Inside flap of original MP44 pouches. We assume the “CON” is the first part of “Continental” (a major rubber and tire maker) as that’s what these flap sides are made from. Guide marks on our cartridge belts.

Guide marks on our cartridge belts.